Seems like once the pattern of reading is finally set, it takes a strong force to make it end. I’m in one of those book devouring phases (partly due to winter), and I have a feeling not much else will be accomplished in the next few weeks! However, I have still managed to tackle creating my first batch of French Onion soup, registering for the ALA Midwinter conference, and hiking 4 miles with my best friend (as well as doing some sort of work every day at that thing called a job). Meanwhile, I moved on from Amanda Palmer to lighter fair, the 1968 fantasy novel, The Last Unicorn, by Peter S. Beagle.

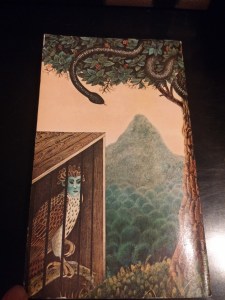

Look at this magnificent 1980 paperback cover! Isn’t it glorious?! Don’t you just revel in it’s dated-ness?

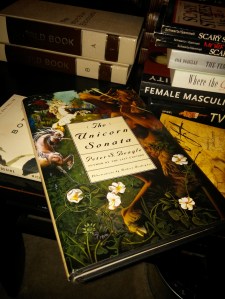

If you’re a child of the 80s or 90s, you’re familiar with the 1982 animated classic featuring the voices of Alan Arkin, Jeff Bridges, and Mia Farrow. I’ve loved this film for a long time, but I am ashamed to say I never read Beagle’s beautiful text…until now. I’ve owned the book for a few years, picked up at the local library’s annual book sale. Back in middle school, my mom gifted me with another of Beagle’s texts, The Unicorn Sonata.

A gorgeous book, it had everything middle-school-me desired: unicorns, detailed paintings, music, and flutes (I loved playing my flute and piccolo at that time, and my mom knew me well). Still, it has been a long time since I’ve experience Beagle’s world, and I was not prepared for the elegant simplicity of his language in The Last Unicorn. I am a true sucker for lovely, tongue-tripping language.

Beagle’s story is a simple one. The Unicorn hears men talking in her forest and knows she may now be the last of her kind. She decides to travel the world to find the truth and hopefully discover the rest of the unicorns somewhere at the edges of the earth. What follows is her journey through a strange and changed world, one that does not recognize her for what she is, except by those who are part of the magic, part of the seeing. She befriends Schmendrick the Magician and Molly Grue, battles King Haggard and the Red Bull, and learns about humanity, love, and all the dangers and joys of mortality.

The simple tale allows the morality of the various encounters to shine. It also allows Beagle to have fun through random character quirks, witty asides, and references to literary and popular culture. He includes an obvious jibe at the tale of Robin Hood while smartly referencing Frances James Child and his ballad collecting. At another turn, a butterfly flits between old and “modern” music. Meanwhile Shmendrick himself seems to be a humble, if somewhat clutzy, version of Tolkein’s Gandalf (though really he is so much more–human at his core with an ancient wisdom beneath his often fumbling power). All of this makes Beagle’s text dance across the page and through the reader’s imagination. I laughed and smiled, and I mourned the turning of the page more than once. Beagle seems to delight in his exceedingly charming cleverness, and really we should excuse him for what he rightfully deserves.

Lastly, it is difficult to describe the language without giving away too much of the tale. It is not the descriptive dreamy language of some, or the poignant metaphorical tome of others. Instead The Last Unicorn contains a childlike flowing nature, simple at its core. Yet rarely will a description of “the dry sound of a spider weeping” make me sigh with sadness. And, how will I ever forget the pain and sorrow of Prince Lir and the Lady Amalthea? The magic exists in Beagle’s ability to make these pieces stand out, imprinted on the memory and heart of the reader. It was hard to return to the real world, carrying these images and words with me, but I am better for it.